Smarter, Better NMB

Diastolic Robotics is developing a better approach to neuromuscular blocker (NMB) drug monitoring and administration.

NMB drugs ("NMBs") relax and paralyse patient muscles (in a hospital setting). Expand

Because they are worried about other important vital signs, anesthesiologists may administer NMBs less perfectly than if they had nothing else to monitor, and less-perfect administration can lead to injury and delay. Expand

Anesthesiologists may administer NMBs on demand: when the surgeon requests the drugs because the patient is resisting the surgery; when the patient is noticed to be fighting the ventilator; and possibly when the patient moves.

Alternatively, administration may be done in an overdosing fashion. With surgical conditions changing or with the patient not responding to the drug as expected, the patient may get too much and be unable to breath at the end of the case.

These styles of administration create risk of intra-operative injury, surgical error and delay, cancelled or delayed cases following due to an inability to leave the OR, and breathing problems, injury and need for additional interventions in recovery.

This injury and delay costs the US health care system approximately $3.3 billion per year. Globally, injury and delay costs can be extrapolated to US$10 billion per year.

We're developing a novel system that measures and adapts to the patient's response to NMBs to assist physicians and help reduce these costs. This system advises the anesthesiologist on the timing and dose of NMB drugs based on modelling of the drug in the patient and the history of the measured patient responses.

Clinical Trial Results

Anesthesiologists may administer NMBs on demand: when the surgeon requests the drugs because the patient is resisting the surgery; when the patient is noticed to be fighting the ventilator; and possibly when the patient moves.

Alternatively, administration may be done in an overdosing fashion. With surgical conditions changing or with the patient not responding to the drug as expected, the patient may get too much and be unable to breath at the end of the case.

These styles of administration create risk of intra-operative injury, surgical error and delay, cancelled or delayed cases following due to an inability to leave the OR, and breathing problems, injury and need for additional interventions in recovery.

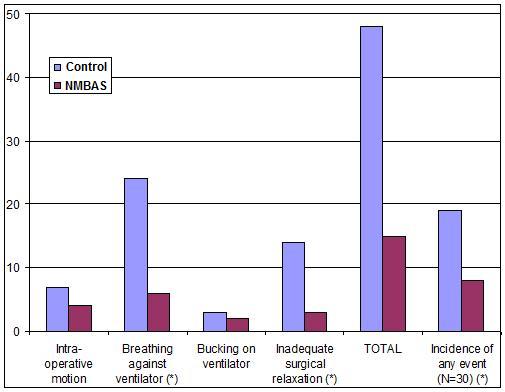

Adverse Events

The incidence in total intra-operative events associated with inadequate NMB was significantly lower for the NMBAS group.

Incidence of breathing against the ventilator and inadequate surgical relaxation were reduced with statistical significance in the NMB treatment group. There was also a trend towards reduced intra-operative motion and bucking on the ventilator, but the difference was not statistically significant.

The incidence in total intra-operative events associated with inadequate NMB was significantly lower in the NMBAS group compared to standard care (8/30 vs 19/30; P = 0.004).

Adverse event results are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Adverse event results from the clinical trial: a comparison of adverse events presented separately (columns 1 to 4), in sum (column 5), and as an incidence per case for the Control (left columns) and NMBAS (columns on the right) groups. The asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance at p < 0.05.

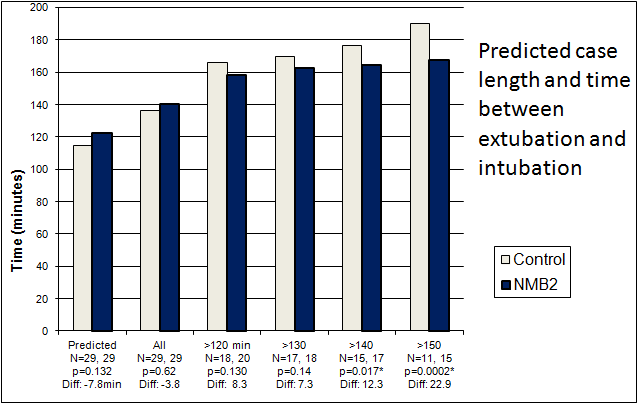

Case Length

NMBAS treatment group cases took less time from patient entry to the room until extubation, despite having a trend towards longer predicted case lengths (not statistically significant however as p=0.132). Time to extubation for the NMBAS treatment group decreased increasingly as cases became longer, with cases of 150 minutes or longer being statistically significantly shorter by approximately 23 minutes.

A comparison of the two groups by procedure length is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Case results from the clinical trial: a comparison of the Control (left columns) and NMBAS (right columns) groups for predicted case length (column set 1) and actual case length. An asterisk indicates statistical significance at p=0.05.

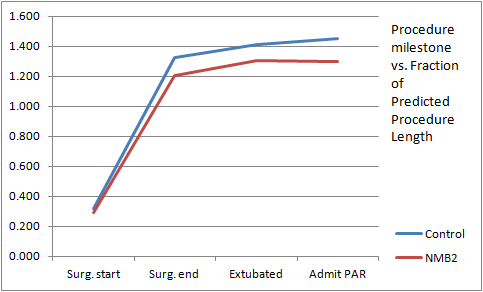

Proportional Case Timing

To correct for the difference in the length of cases when comparing the two groups, the recorded time to reach procedure milestones was normalized by calculating the data as a proportion of the expected length of case. The value for the expected length of case was the

Figure 3 shows the results, where the groups have similar surgical start times of approximately 0.3 (30%) of the expected case length, but overall the NMBAS group cases proceed relatively quicker. After surgical start ("Surg. start"), the group timing diverges with the halting of surgery requiring NMB agent ("Surg. end") occurring at 1.33 times the expected case length for the Control group and 1.20 times the expected case length for the NMB treatment group. Extubation ("Extubated") occurred at 1.41 and 1.30 times the expected case length, and admission to the Post-Anesthesia recovery room ("Admit PAR") occurred at 1.45 and 1.29 times the expected case length for Control and NMBAS treatment groups respectively.

Figure 3: Timing results from the clinical trial: a comparison of the two groups for time to case milestone by proportion of the predicted case length.

Details of the clinical trials have been published and can be found in brief, here:

Pubmed Extractand in the peer-reviewed journal Anesthesia and Analgesia, here:

Anesth Analg 2008 107 p1609Patents Awarded

Patents awarded for diarobo's NMB projects include:

- US 8,506,502 Sensors and sensing for monitoring neuromuscular blockade

- US 8,229,872 Modeling and Control for Highly Variable and Nonlinear Systems

- CA 2,665,121 MODELING AND CONTROL FOR HIGHLY VARIABLE AND NONLINEAR PROCESSES

- CA 2,664,172 IMPROVED SENSORS AND SENSING FOR MONITORING NEUROMUSCULAR BLOCKADE

Patents Applications

Applications are being pursued as continuations and/or divisionals of the above in the United States and in other countries.

The initial applications are: